“Cultural matters are integral parts of the lives we lead. If development can be seen as enhancement of our living standards, then efforts geared to development can hardly ignore the world of culture.” – Amartya Sen

Often, when the word culture is mentioned, many people’s minds turn to drumming, dancing and other rituals performed during special occasions such as festivals, traditional marriages and funeral rites. Believe it or not once upon a time, a chairman of Ghana’s then Commission on Culture had described culture as “something we do for leisure!” This short sighted perception of culture is still prevalent today and is a serious threat to our individual and communal development efforts. It is important to recognize that although drumming and dancing are important aspects of culture, they are by no means the defining elements or the most important. In other words, they do not tell half the story of culture. This fixation on drumming and dancing portends trouble for our future growth and development. Here, I wish to direct a few questions and inquiries to the Bulsa in hope of broadening our scope, for as we say, when a stone is falling from the skies, everyone covers their own head (Tain dan nyini won cheena, wa meena a tuk ka wa zuk).

First, I would like us to answer a fundamental question: who are the people called Bulsas? Or who is a Bulsa? This question is crucial because a faithful and true answer to it is also the definition of Bulsa culture. For those of us who are literate, the question may cause us to think about the different narratives on the origin of our people but that is not where the answer lies. The answer lies in the ideas, values, beliefs, rules, and material dimensions of the Bulsa people. It is through these that we derive our sense of self. These are the things that define us as a people; that set us apart from others and that enable us to relate to other people and to coexist with them.

Culture and Persona: Two Sides of the Same Coin

Each of us draws a major part of our sense of ‘self’ from the cultural group in which we grow up and are socialized. Research has demonstrated that culture tends to create and support ‘basic personality types’. Cultural factors influence lifestyles, individual behaviour, consumption patterns, values and life goals. Without a proper understanding of who we are, our self-respect, personal confidence and self-esteem suffers. Stories of Bulsa outside Buluk who were embarrassed by their Bulsa origins or who were intimidated by their more confident and culturally assured colleagues from other parts of Ghana are almost proverbial. In fact, such episodes are still being acted out today by many Bulsa all over Ghana. The main reason why people try to hide their ethnic identity is that they are ignorant about who they are! Thus these our Bulsa mates may have no idea of who or what a Bulsa is. They feel overwhelmed because they have lost the security and support of their native culture and are not able to integrate into another culture. A person in this state is often at risk of poor mental and physical health.

Many of us reading this may scoff at our less self-assured compatriots and would beat our breasts and say: ‘I am proud of my Bulsa roots or I am proud to be a Bulsa’. This however does not solve the problem. Without a proper understanding of the values, customs, ideas, beliefs, and material dimensions of our culture every one of us will feel intimidated at one point or the other not because we are not proud of our origin and identity but because we are not sure we can say anything about ourselves beyond the rhetoric that we are ‘proud’ to be Bulsa. How can we even be sure it is pride that we feel when we are not sure of what we are proud of? More importantly, how are we preparing our future generations to understand their culture and to be culturally assured and thus proud of their identity?

Having served as a teacher in at least three different schools in Sandema between 2003 and 2009 I have made certain observations that trouble me. When you ask a student to make a simple sentence, you are most likely to hear: “Kofi is a boy” or “Ama is going to school”. I once asked students to describe their best friend and everyone started with something like ‘The name of my best friend is Kofi, Ama, Aku, Mensah, Kojo etc’. When I asked them what about Adjuik, Amoak, Abuuk, Ayomah, Akansiing, Awogtalie, Atangbain and co, everyone burst out laughing “Ah master paa, how can our friends be called by such names”. Ask students to write any story they know and you will read titles like: ‘Ananse and the pot of wisdom’ or ‘Why Ananse lives in the roof of the house’ etc. Nobody remembers Asuom, Apiuk, Akalaasing and the other heroes of Bulsa tales. Of course in all these, we cannot blame the students. Their textbooks, readers and teachers alike all teach them so. Where are the Bulsa educationists? Are our teachers parrots who simply repeat what they hear or read from the textbooks for the pupils? No they are not. I can attest to that because I know many teachers who are making great efforts to adapt and modify what their pupils learn. I salute their individual and school based efforts.

But as a people, what efforts are we making to ensure that our children can actually learn something about their origin and culture that will give them the confidence and self-respect that they need to fight for their place in this world? Are we just waiting to be subsumed by other ethnic groups? No we cannot afford to. But without an understanding of who we are, through an understanding and appreciation of our culture, we will never be able to live fulfilling lives. We will always feel uncertain about ourselves. We will never be able to achieve our personal let alone communal goals.

This quote from UNESCO succinctly captures the spirit of my brief thesis.

“Deep in our hearts, we all understand that the quality of our lives depends, to a great extent, on our being able to take part in, and benefit from our culture. We instinctively know, with no need for explanation, that maintaining a connection with the unique character of our historic and natural environment, with the language, the music, the arts and the literature, which accompanied us throughout our life, is fundamental for our spiritual wellbeing and for providing a sense of who we are”.

Culture Enables and Drives Development

Besides the personality development and self-actualizing role of culture culture is the perfect starting point and mechanism for linking people to the national development process. Cultural heritage protection is a tool for building understanding, respect, love, cohesion, and community development. Local understandings and interpretations of a community’s history feed into and partially drive the demands, aspirations, sentiments, and interests of present and future generations. Hence, by paying attention to, and incorporating these understandings and interpretations, more effective community development can be achieved. Also, culture is like the fountain of our creativity and progress. If it is carefully nurtured, our full potential in creativity and innovation will be unleashed. The creative industry is one of the fastest growing industries worldwide today.

Culture also provides a sustainable economic resource in which communities are empowered in their own economic development. Today, cultural preservation has gone global. Many landmarks, ancient structures and sites of historical importance across many countries worldwide are being catalogued and preserved as ‘world heritage sites’. These sites generate large amounts of economic resources that support local and national development. Promoting sustainable tourism as a sub-sector for investment encourages investments in infrastructure and stimulates local, sustainable development. We know that many sites and land marks have played significant roles in the history of the Bulsa but what has become of them? Similarly, many articles and artifacts of historical importance are being thrown away or sold if they still have any economic value. Investing in the conservation of these cultural sites and assets, promoting cultural activities and the traditional knowledge and skills developed by our forefathers is an effective means towards environmental sustainability and development. Tourism can be the breakthrough as a source of revenue for our poor homeland.

Undoubtedly, some of our cultural values, traditions and goals are not very useful today. This however is not an excuse to throw away the bad water and the baby together. Even the not so useful aspects serve as signposts for guarding upcoming generations and may be preserved in some form for reference and study. The preservation of culture is necessary to stimulate, excite, inspire, and drive development. Without enough effort at preserving our culture, we stand in danger of losing our identity; we and our children will forever be left wandering in the fringes of Ghana’s history, ignorant or at best, uncertain and afraid of who we are.

The Bulsa Heritage and Cultural Society (BHCS) – Help us save our heritage!

The idea of building a museum in Buluk to preserve at least some of the material dimensions of our culture is not a new one. Many possibilities have been attempted in the past but now seem to be slipping out of mind. However, the importance of a true understanding and appreciation of our culture to the individual and communal development of the Bulsa land means that such a project should not be allowed to slip out of mind.

The Bulsa Heritage and Cultural Society (BHCS) is a nascent project by concerned sons and daughters of Buluk. The idea was inspired by a small Bulsa museum put together in Germany by one of the foremost anthropologists who studied the Bulsa people and put our name on the world map; Dr. Franz Kröger. This man has written so much about and for the Bulsa in articles and books including a Buli-English Dictionary and has a large collection of Bulsa articles acquired over his many years of study (cf. Buluk 9, p. 22). He has also produced a large and comprehensive catalogue of articles and artifacts from Buluk that is guaranteed to astonish even the most disinterested observer. Many of them are no longer ordinarily seen in Buluk and may have become lost or sold. These are now being displayed in the small museum in Germany. Taking a leaf from his book, we have started something small instead of waiting for our traditional and political leaders to build us a museum which may not become a priority for them within the next half century.

The Plan

The plan of the society is to unite a number of individuals who are committed to the idea of preserving our cultural heritage. Members will make voluntary contributions in cash or kind at their convenience and this money will be used to acquire materials of cultural value either new or old and stored as a private collection. It is not a business or even a community project. The society has just been introduced to the paramount chief in Sandema but as yet has no links with the political leadership of Buluk. It is hoped that, when a reasonable amount of articles are gathered, they can be exhibited during the annual Feok festival celebration in Sandema.

Procedure for Acquiring Articles

Art works and artifacts or materials may be bought or received as donations. Old and worn out things are particularly of interest but we will also buy or receive new articles. For some historical articles, permission will be sought from the Regional Museum to acquire and exhibit them. Items of questionable origin (stolen, forcefully taken or outlawed products) shall not be accepted. All items bought or received shall be named and labeled appropriately.

Work Done So Far

Many sons and daughters of Buluk have already bought into the idea and have made contributions in cash and kind. A lot of labour has been spent on acquiring some materials. Dr. Franz Kröger, the aforementioned anthropologist, has consented to be a patron to advice and guide the collection and labeling of articles and has already made available his complete catalogue for the use of the society.

The society has already acquired several material objects and aim to increase the collection in the coming years: see table below.

Way Forward

Contact will be made with political and traditional leaders in Buluk to seek their support and blessings in due course but the project will continue to be a private collection until such a time that it becomes necessary to hand it over to a public institution to take care of.

Some renovation works have been started on the ‘chief’s old court’ (stone structure in Sandema) and enquiries have revealed that this is the work of a group called ‘Abil dogdem’ (Sons and Daughters of Abil-yeri) who intend to present it as a Museum to the motherland. We of the BHCS commend them for this excellent initiative and call on all and sundry to support the project to succeed. We look forward to working with them.

What is Needed?

What is needed is a desire to see the heritage of Buluk preserved for future generations, a willingness to make a small donation (any amount), a little tolerance for risk and a little patience to wait for results over time. As the project is still early and developing, we are also interested in suggestions and ideas that can help direct and promote it. Please contribute constructive ideas and support to help the project succeed.

How to be Part of It

For further enquiries or to make a contribution to be part of this initiative, you may contact the following people:

John Agandin (Accra) – 0208566440/j.agandin@yahoo.com/ agandinjb@gmail.com

Martin Akandawen (Accra) – 0507176405 – martinakandawen@gmail.com

David Angaamba (Sandema) – 0242776788/ davidangaamba@yahoo.com

Cornelius Adumpo (Sandema) – 0203952142/0246144606/ adagmi@yahoo.com

Priscilla Animi (Kumasi) – 0501340250/ animipriscilla1982@yahoo.com

Katherine Lamisi Asemiteng (Kumasi) – 0206476581/ asemiteng.kate@yahoo.com

Franz Kröger (Lippstadt, Germany) Franz_Kroeger@t-online.de

There is an intrinsic value of culture to a society, irrespective of its level of development which cannot and should not be allowed to elude us. This value makes the development of culture a development outcome in itself. We can realize this development outcome, let us do it together!

| Photo | Buli and English name | Function, meaning, productgion, origin |

| nabiin(g)-soruk, pl. nabiin sortachain of Rosetta beads | Only worn at funerals by male and female close relatives of the deceased;The pearls were perhaps produced in Venice or another European town. They were used by the colonialists to exchange them for gold, slaves, ivory etc. |

| pung, pl. pinalit. “stone, rock”marble upper arm bangle | Worn on the upper arm as decoration by men and women and (in the past) by warriors to give a thrown spear or a beaten axe more power.The marble stone is only found in the Hombori Mountains (Mali).Made by Bulsa or imported from neighbours (?) |

| nang-waab,pl. nang-wiimairon (brass??) anklet | Anklet, worn perhaps originally around the ankle by horsemen as a kind of spur.Later it became a pure piece of ornamentation. |

| bang-gatuk,pl. bang-gatusa,or bang-gbing,pl. bang-gbinatrimetallic bangle | made by Bulsa blacksmithsalso used as wen-bangsa (bangles on a bogluk) |

| nisa-bang,pl. nisa-bangsabrass (bronze) bangle (bracelet) | worn as a mere piece of ornamentproduced in the lost-wax techniqueimported or made by a Bulsa bronze caster(in modern times the only workshop has been in Sandema-Choabisa) |

| longi or logni, pl. longa,bell, bobbin bell, brass/bronze bell | worn e.g. by horses and donkeys making it easier to find them;used by some soothsayers;worn by the youngest son of a deceased man at the Kumsa-funeralproduced e.g. by the Choabisa blacksmith in the lost-wax technique |

| zu-chiak, dial. zu-kiak, pl. zu-chaasa/ zu-kaasahorned war-helmet(here: buffalo-horns) | today only used for war-dances (e.g. at the Fiok-festival or at funerals);the cap is producedby coiling kpinkpiak grasses and using toboga-grass as the active thread. |

| kpaani, pl. kpaanabattle axe with a toothed iron spike resembling a big arrow head,pyrographic decoration (modern influence) at the handle; barbs in one direction | old weapon used in battles by Bulsa warriors,today only used in war dances without the spike |

| tacheng, pl. tachensatobacco pipe with wooden head(modern form) | after the introduction of tobacco it was smoked only in pipes by men and old women; wooden bowl decorated; in the old types the bowl is made of fired clay. |

| kpaam-kabook,pl. kpaam-kabootalid: naliklidded ceramic vessel with black ornaments | container for sheabutter, in possession of woman,also for dried meat, ochro, bumbota etc.associated with many taboos;a married woman’s kpaam-kabook is destroyed on a footpath (leading to her parents’ compound) on the 4th day of the Juka-funeral.(in Sandema also other types of ceramic vessels are used). |

| chin, pl. chinacalabash bowl | Calabash bowls may have manyfold functions: for eating saab (T.Z., millet porridge) or, for drinking millet beer (daam). Calabashes with a short handle (see photo) are also used for ladling the hot millet porridge. |

| tuik, pl. tuisasmall wooden mortar | This small type of mortar can be found in nearly every traditional household, but there is usually only one big mortar in a compound.Used for pounding soup ingredients, groundnuts, jong, biila, buura, medicine etc.Bulsa also use it for removing the spelt from rice grains (from millet usually in the big mortar). |

| tandung, pl. tandungsawooden pestle | used for pounding in the small mortar (for the big mortar a longer pestle is used), see: tuik |

| nueri(k), pl. nueplastering stick, wooden bat | This bat is only used by women for beating the plastered inner courtyard. Young and strong women use new and heavy nueri, old and weak women a lighter and more worn-out one (see photo). The light and worn-out bat is also preferably used for the first beating (piisika), the heavy one for the final treatment after the sand, gravel and mud have been applied. |

| ngabik or ngma-barimwickerwork fish trap | A fish can enter the cage-like basket only through a small entrance.These traps are placed in a running water with the opening against the current and fixed by a stone or a stick driven into the ground. The trapper controls his trap every 1-3 days.The trap is suited for the following types of fish: siuk (lungfish? mud fish? Protopterus annectens?), paaring (Tilapia sp.), sinsalik (Labeo senegalensis? Epiplatys sp.? Alestes sp.?) and balingi. |

| yalung, pl. yalungtasmall basket made of grass | used for short-time-storing of smoked meat, fish, dawa-dawa (jong), salt, pepper etc.also used as a sieveoften placed on the outside wall of a “room” (dok) |

| pak, pl. paksaplaited cords made from thin grass (pak) | used particularly for female waist-stringsundyed: worn by young girlsred /lilac: worn by womendark blue/ black: used in the poi-nyatika ritual |

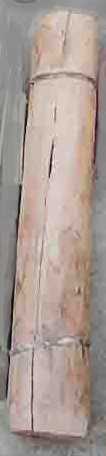

| kazagsa (sing. kazag rare)fibres from Deccan hemp or Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus) | The plant is grown in or near millet fields.After peeling the stems the reddish bark is beaten and rubbed to remove all the woody particles. Then the fibres resumes a whitish colour.Kazagsa-fibres are used for making twisted or plaited ropes or the zaaning-container for calabashes (see below). |

| sie (pl.), siri (sing) denotes one stalktraditional broom / brush (bundle of sie or ngmining stalks | Every morning, before the other inhabitants get up, a women sweeps her inner courtyard with such a broom. The stalks of the broom can be used in a spread or compact shape.For sweeping flour in the grinding room a short sie, called nanzuk-sie, is used. A thin sie-brush can be used for sprinkling the ngam-liquid on outside walls to make them resistent against rain. |

| miisa-vaata (pl.)traditional apron made of fibre strings | in the past worn by women on the waist-string in front and behind; today still worn over the cloth dress at funerals |

| jiuk, pl. jiuta(lit. “tail”), fly whisk, flyswitch;magical object | rarely used as a fly whisk;more important is its magical function and as an object of prestige. Magical substances may be kept in the handle. At a Kumsa-funeral mats and other things may be “wiped” with these tails to ritually clean them. |

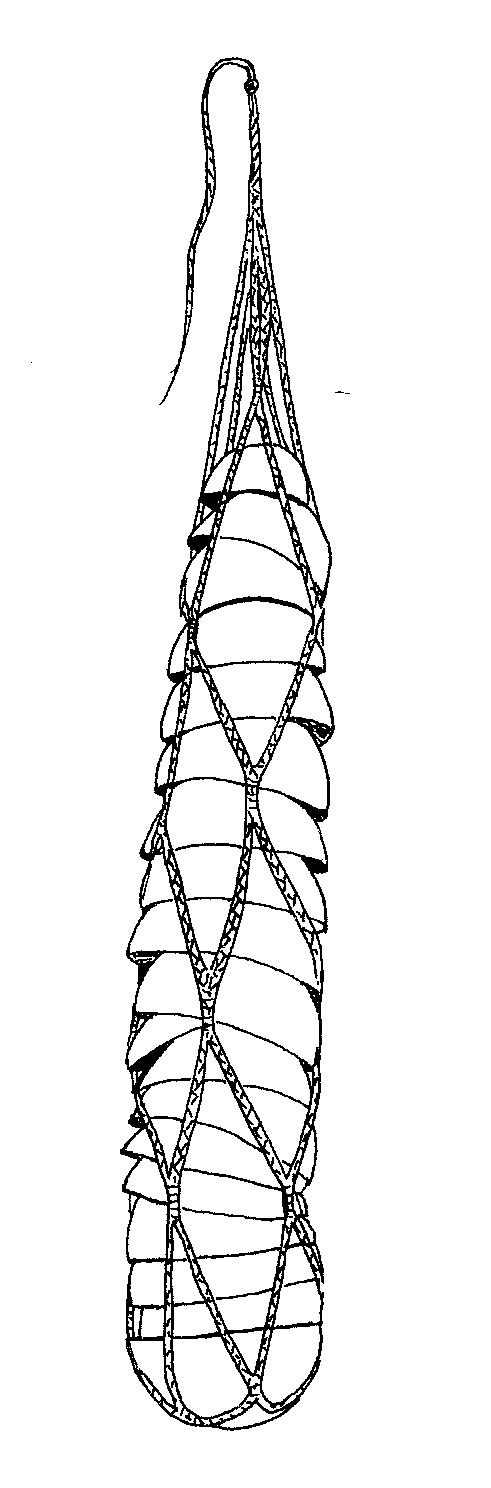

| zaaning, pl. zaanisa long and wide-meshed net made of ropes |  container for piled up calabash bowls, property of a married womanassociated with many taboos,men are not allowed to open it;in the lowest calabash the valuables of the woman were hiddenleft: zaaning with calabash bowls container for piled up calabash bowls, property of a married womanassociated with many taboos,men are not allowed to open it;in the lowest calabash the valuables of the woman were hiddenleft: zaaning with calabash bowls |

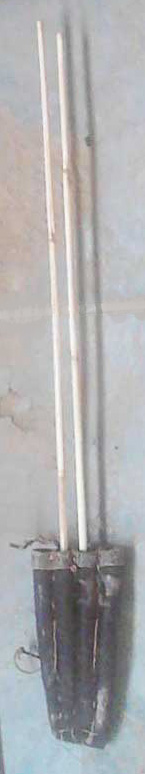

| left: namarik,pl. namarisaarm-quiver right: lok, pl. loktawooden cylindrical quiver | namarik: worn on the left arm; poisoned arrows used for immediate usehere: 4 pockets, others have fewer or more pockets lok: storage of arrows, not always poisoned,production: a log is split into two halves; each of them is hollowed with a hatchet, then the two halves are glued and bound together |

| tom, pl. timabow (weapon) | used for hunting and (in the past) for warmade from the wood of the yuelik-tree, rarer of the goari-tree; string: bamboo; indirect bow string attachment |

| bang, pl. bangsaflat brass bangle | cast in the lost-wax technique;made by Bulsa or imported? |

| bang-mieni,pl. bang-mienatwisted bangle, or:bang-gbing, pl. bang-gbinabangle with loopshere: twisted iron bangle with 6 loops | Iron bangles (smooth or twisted; straight or with loops) are made by Bulsa blacksmith. They are often prescribed by soothsayers and usually have a religious or magic meaning. |

| ni-felin, pl. ni-felimafinger-rings of different forms and material | finger-rings may be loaded with a magical power or they just serve as ornaments;traditional finger-rings are traditionally worn on the middle finger or ring-finger of the left hand of a man. |

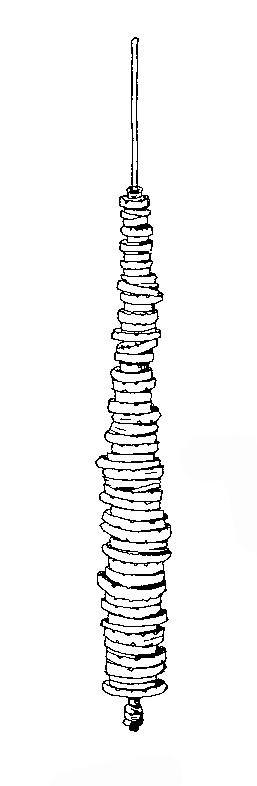

(no photo yet) (no photo yet) | kayagsa (pl.); sing. kayak denotes one diskrattle consisting of many small peroforated disks stringed on a stick; disks inecrease in size fromthe upper to the lower part.disks arranged in pairs: a concave disk lying on another concave disk encloses a resounding hollow | shaken (nagi) only by girls or young women by vertical and sideways movements without any accompanying other instruments or songs. Two or three kayagsa may be shaken together. Although this rattle is not a typical “talking instrument”, some simple messages can be played on this instrument.The rattle may only be played during the time of sowing and harvesting millet, not in the time of germination. |